Tuesday, November 16, 2010

Final words (DB)

Sunday, October 31, 2010

Karen Elaine Spencer - sittin'

he asked me what i was doing here. i replied, "working." i then contextualized this by saying i was doing research, embodied research, researching what it was to be a stationary presence within a place of transit. he accepted my explanation saying if there was anything i needed, they were always here.

Saturday, October 30, 2010

Carlos Monroy, St. Lawrence Market, Saturday October 30, 2010 (NL)

I approach the St. Lawrence Street Market from Union Station. It is slightly chilly on this second to last day of the festival. I am looking for the CMG Performance Art Services booth, which has been described to me as an organization by and for artists, figure-headed by Columbian artist Carlos Monroy, that promises to make performance art more economically accessible while giving performance artists a regular source of income. I am intrigued…

In both, the work for sale is separated into four categories: Temporary and Ritualistic; Public Spaces; Minimalistic and Formalstic; Identity Issues Related; Institutional Critique. I am leafing through a performance art library ready to be bought and sold for my aesthetic pleasure. Looking for something to brighten up your corporate retreat this year? Purchase some performance art, all tied up in a lovely corporate bow.

CMG Performance Art Services is sold as a brand identity. However, while not completely convincing as a business pitch, it works as satire. As I lean in,

Furthermore, Monroy continues, CMG Performance Art Services is, like many contemporary businesses, committed to public outreach and education. In categorizing the product into “five styles of performance” the public is invited to think about an anatomy of performance art. To recognize genre distinctions within a notoriously difficult to understand artistic form.

With Joseph Beuys’s famous dictum “everyone is an artist” as the ground of his project, he asks each passerby to join the flock, believe in the cause, and network – for a small fee – in the name of performance.

Berenicci Hershorn, XSPACE, Saturday October 30, 2010 (NL)

As I head down the stairs to XSPACE’s basement area, XBASE, I hear a faint digital soundtrack that manages to entice me and make me uneasy all at once. It is high pitched and rhythmic, like the clicking and beeping of some alien Pigmy music. At the far end of the basement Berenicci Hershorn stands in a clear plastic enclosure, bright spotlight behind her. The plastic gives the performance a danger-zone feeling. Her smock has a large black decal at the chest, and for the life of me I can’t help thinking that it looks like the headdress of a HAZMAT suit. Whatever is going on behind the plastic is meant to invoke toxicity. Or messiness. Or something dangerous. To my left, as I stand before the plastic enclosure, is a huge mountain of ice piled inside of a large chalk circle. It glistens under a white spotlight like a mound of oversized diamonds. In the center of the space is an old tin kettle, boiling on a plinth and lit by a tiny red LED. It also stands inside of a large chalk circle. We are privy to a ceremony of some sort, but whether it will end in mercy or malice I am not sure.

As I head down the stairs to XSPACE’s basement area, XBASE, I hear a faint digital soundtrack that manages to entice me and make me uneasy all at once. It is high pitched and rhythmic, like the clicking and beeping of some alien Pigmy music. At the far end of the basement Berenicci Hershorn stands in a clear plastic enclosure, bright spotlight behind her. The plastic gives the performance a danger-zone feeling. Her smock has a large black decal at the chest, and for the life of me I can’t help thinking that it looks like the headdress of a HAZMAT suit. Whatever is going on behind the plastic is meant to invoke toxicity. Or messiness. Or something dangerous. To my left, as I stand before the plastic enclosure, is a huge mountain of ice piled inside of a large chalk circle. It glistens under a white spotlight like a mound of oversized diamonds. In the center of the space is an old tin kettle, boiling on a plinth and lit by a tiny red LED. It also stands inside of a large chalk circle. We are privy to a ceremony of some sort, but whether it will end in mercy or malice I am not sure.

Hershorn’s action is repetitive. For the duration of the evening she stands behind a long kitchen table wearing a white smock. Methodically, she removes a piece of newspaper from a pile, folds it in preparation, and places it in the center of the table. She then pours a dollop of a red viscous material (paint?) from a tin watering can into the center of the newspaper and gently folds it into a little packet. Each folded newspaper is a feat of Origami. Gently she ties the packet with a piece of twine and places it at the top of the table. In between each action Hershorn cleans the space. The pile of red liquid packets accumulate as the performance moves from its first into its second into its third into its fourth hour, some seeping through, some retaining their integrity. Fold. Pour. Tie. Place. Clean. These are the five actions that Hershorn repeats and repeats. The steam from the kettle, meanwhile, permeates the space with a faint something – I can’t quite tell what. The smell is soothing, in stark contrast to the sound and the site of Hershorn herself, who I find determinately unsettling as I inhabit her symbolic universe in its fastidious and unremitting continuity.

Hershorn’s action is repetitive. For the duration of the evening she stands behind a long kitchen table wearing a white smock. Methodically, she removes a piece of newspaper from a pile, folds it in preparation, and places it in the center of the table. She then pours a dollop of a red viscous material (paint?) from a tin watering can into the center of the newspaper and gently folds it into a little packet. Each folded newspaper is a feat of Origami. Gently she ties the packet with a piece of twine and places it at the top of the table. In between each action Hershorn cleans the space. The pile of red liquid packets accumulate as the performance moves from its first into its second into its third into its fourth hour, some seeping through, some retaining their integrity. Fold. Pour. Tie. Place. Clean. These are the five actions that Hershorn repeats and repeats. The steam from the kettle, meanwhile, permeates the space with a faint something – I can’t quite tell what. The smell is soothing, in stark contrast to the sound and the site of Hershorn herself, who I find determinately unsettling as I inhabit her symbolic universe in its fastidious and unremitting continuity.

Over the course of this five-hour performance, Hershorn invites us to experience something between the production of bio-weapons of mass destruction and a Voodoo high-priestess' ritual. As her smock becomes smeared with blood-redness, the enormous pile of ice (I wouldn’t be surprised to find out that it is 40 or 50 bags worth) begins running a river of water towards the front of the space. I watch the water in two forms, the ice on the floor and the steam from the kettle, transforming and moving through space. I watch Hershorn making her little tied packets of blood-not-blood, ready to post or send or scatter to whichever corners they are destined for. I watch all of these things to the sound of the electronic alien Pygmies, and leave the space for the final time, as I began: vaguely unnerved.

Roddy Hunter, Through Michael Fernandes, Toronto Free Gallery, Friday October 29, 2010 (NL)

My day starts, again, by going to the Toronto Free Gallery at noon to meet with Michael Fernandes and witness his ongoing Doing Things With Strangers. For four days of the festival, loosely between the hours of noon and five, we have all been put on alert: Michael Fernandes is performing in and around the Toronto Free Gallery. Because of this, we have all watched his actions – sitting in on the afternoon Performance Art Daily talks, wandering the streets interacting with business owners, asking an artist where she is from and what kind of work she does, sitting in a cafe over coffee - with attention. All these things have both been constituted as performance and as a question: is he performing? Up until today – so for the first two and a half days of the performance – this has been maintained actively as a question, with Fernandes offering only his enigmatic look or wry smile when asked when/where are you performing?

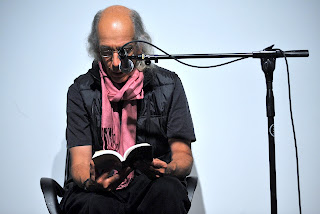

Today starts much the same: I arrive at the gallery and notice him sitting, ready for this afternoon’s Performance Art Daily, a talk by UK artist, critic, organizer and teacher Roddy Hunter. Despite myself I, too, want to go up and ask Fernandes if he's performing this afternoon. Though that question seems increasingly antithetical to what he's doing, as someone tasked with writing about the piece a part of me wants to know for certain: is this it or not? Am I supposed to be writing about what's happening now or not? Sitting down for Hunter's talk - Notes Towards the Eternal Network in an Era of Globalization - I find myself listening through the lens of Fernandes’s Doing Things With Strangers.

Hunter starts us off with an autobiographical sampler of his performances over the last 20 years. We are treated to an onslaught of works – 30 or 40 – each represented by a single image and brief description. What is central here is not so much the work or its genesis but instead the geographical location of each work, detailing a chronogeography of art actions: Hungary. Kazakhstan. Japan. Berlin. Transylvania. Toronto. Serbia. Poland. Taking off just his left shoe and sock he navigates these art actions for us, bringing our attention to the interrelationship between forms of visibility (art actions) and forms of capitalism - the circulation of economic, social, cultural and symbolic capital as constitutive of contemporary networks including those of the performance art festival.

Hunter’s central terms for this analysis come from sociologist Henri Lefebvre, particularly his distinction between “the global” and “the mondial.” While the global - and, by extension, globalization - refers to a totality, to an effect, the mondial and mondialisation refer to a making practice, to a making and remaking of worldwide space. The mondial - multiple, fractured, process-driven - gives rise to the possibility of parallel worlding practices. It is in this context that Hunter wants to question performance art… What world are we building when we organize, dis-organise and re-organize international performance art festivals and traffic in the circulation of international performing bodies and the dissemination of local cultural (performance) discourses? In other words, how do we as performance artists inhabit capital? Is it possible, he asks, that artists in the performance art network, traveling everywhere, themselves articulate a form of aesthetic neo-colonialism? In this context, Doing Things With Strangers becomes the fear that the stranger will become obsolete. That instead of trafficking in difference, the performance art festival circuit will work only to increase sameness. While concerned with what he dubs a kind of neo-liberal colonialism, the network - a figure of possibility for Hunter, riffing on George Brecht and Robert Filiou - is nonetheless what can be mobilized to replace the outdated concept of the historical avant-garde in thinking about these practices. While the historical avant-garde is a category dependent on a rejected mainstream, the network, like the mondial, becomes a figure for living in the same world, but living in it differently - in effect replacing a binary with a rhizomatic figure. Hunter's talk, experienced in the context of Fernandes and Doing Things With Strangers, recalls for me the term altermondialisation, not just as an umbrella term for activists advocating alternate forms of globalization, but also as it is mobilized by feminist theorists and philosophers like Donna Haraway, Rosi Braidotti, and Beatriz Preciado. Altermondialisation takes seriously the ethics and the aesthetics of worlding practices so dear to both Hunter and Fernandes – to Fernandes through Hunter, Hunter through Fernandes, each in different idioms, different densities and textures of practice.

After the talk I mill around, following Michael Fernandes in his "other-worldalisation," at a a distance, feeling like a performance art stalker. On duty but not wanting to interfere, I watch him go up to one person – a stranger? – and strike up a conversation. I watch him bum a cigarette from another. After a while I stand next to him and, when there is a lull in the conversation, I break down and gently ask the question I have been enjoying not knowing the answer to: whether he is performing this afternoon. He gives me a look. People keep coming up to me and asking whether I am performing. They say “where have you been? I have been looking for you performing and haven’t been able to find you.” You know what I tell them? You don’t need to look for me, I am here! I am right here! This is it! I nod and step back to observe again. The performance has shifted from an enigmatic question, is this performance?, to a forceful assertion, this is performance!

I am left with the question, what kinds of other-worlding are being practiced here? What multiple, fractured, process-driven, making and remakings of worldwide space? What parallel worlding practices? A Dick Higgins quotation from Hunter's talk is haunting me: “[C]offee cups can be more beautiful than fancy sculptures. A kiss in the morning can be more dramatic than a drama by Mr. Fancypants. The sloshing of my foot in my wet boot sounds more beautiful than fancy organ music.” Doing Things With Strangers, however, is not about a (perhaps not so) simple engagement with what the lens of performance can offer to the practice of daily life, but more emphatically about the role that performance can play in creating new lines across social difference. After a half an hour or so, I see Fernandes leave and I let him go, unencumbered by my nosiness, off into a world of strangers.

Karen Elaine Spencer - sittin'

if you come to see me but cannot find me, does this mean you missed my performance? this is not my question. if you come to see me but cannot locate me, my question is, "what does this produce?"

Friday, October 29, 2010

Pancho Lopez, Anger, XSpace, Friday October 29, 2010 (NL)

It shatters.

Champagne splashes and runs across the gallery floor, its rich odor filling the air as the audience scrambles back a little, and the gallery staff come in to prepare for the next performance.

Michael Fernandes, XSpace, Friday October 29, 2010 (NL)

Fernandes sits quietly in the space. An amplifier buzzing and a microphone in front of him.

He leaves. We clap.

Irma Optimist, Performance Connection, XSpace, Friday October 29, 2010 (NL)

She holds up a compact piece of paper, the size of a small boulder, crumpled and roughly painted black. After presenting it to the audience, much as a magician might show his hat for all to see that there is nothing in it, she slowly unfurls it making gentle crumply sounds, revealing a white plane that emerges from within the three dimensional black dot. Continuing to work with the sound of the paper – rustling and crinkling – she eventually works it until it is totally open. Not quite flat, she shows it to us as a drawing. A flag – all white with one black dot. She clothes-pins it to the red ribbon. Another ball is presented and unfurled. She repeats the action. This time the dot is a little lower, our attention brought to the variation of small differences.

She holds up a compact piece of paper, the size of a small boulder, crumpled and roughly painted black. After presenting it to the audience, much as a magician might show his hat for all to see that there is nothing in it, she slowly unfurls it making gentle crumply sounds, revealing a white plane that emerges from within the three dimensional black dot. Continuing to work with the sound of the paper – rustling and crinkling – she eventually works it until it is totally open. Not quite flat, she shows it to us as a drawing. A flag – all white with one black dot. She clothes-pins it to the red ribbon. Another ball is presented and unfurled. She repeats the action. This time the dot is a little lower, our attention brought to the variation of small differences.  Repeat again. The unfurled sheets of paper are beautiful, all crumples and shine in the gallery light. She repeats the action seven more times, ten in all, each time presenting the ball and treating us to a soundscape of crumple as we witness the movement of one material – paper – between two states. The pages hang like ink stained laundry. Black on white on white almost completely covering the ribbon's line of red, which now exists only at the edge.

Repeat again. The unfurled sheets of paper are beautiful, all crumples and shine in the gallery light. She repeats the action seven more times, ten in all, each time presenting the ball and treating us to a soundscape of crumple as we witness the movement of one material – paper – between two states. The pages hang like ink stained laundry. Black on white on white almost completely covering the ribbon's line of red, which now exists only at the edge. Dropping the centers one by one to the floor, we are presented with ten hanging voids. Then Optimist hides the scissors in her skirt and pulls each sheet down with a firm tug that sends the clothespins flying. When she is done she places them, one by one, around her neck – a 17th century ruffle grown to comic proportions.

Dropping the centers one by one to the floor, we are presented with ten hanging voids. Then Optimist hides the scissors in her skirt and pulls each sheet down with a firm tug that sends the clothespins flying. When she is done she places them, one by one, around her neck – a 17th century ruffle grown to comic proportions.Henry Adam Svec, Songs Just For You, XSpace, Friday October 29, 2010 (NL)

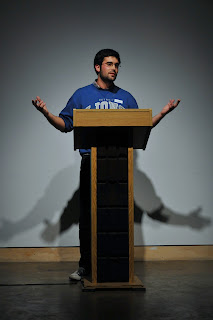

Svec begins to sing. He stops. I am not drawing your attention to the songs themselves, he says, I am not sure if the songs are authentic, I am bringing your attention to the singing of them. He sings a lonely song called “Don’t.” One line from the song stays with me – although he did tell me not to pay attention to the content: If you think this is just a game I am playing, if you don’t think I mean every word I am saying. The words might as well be a commentary by Svec, as I for one have oscillated between taking him seriously and taking the whole thing as a sly critique.

Svec begins to sing. He stops. I am not drawing your attention to the songs themselves, he says, I am not sure if the songs are authentic, I am bringing your attention to the singing of them. He sings a lonely song called “Don’t.” One line from the song stays with me – although he did tell me not to pay attention to the content: If you think this is just a game I am playing, if you don’t think I mean every word I am saying. The words might as well be a commentary by Svec, as I for one have oscillated between taking him seriously and taking the whole thing as a sly critique.Francis O'Shaughnessy & Sara Létourneau, I have nothing to say about my day, XSpace, Friday October 29, 2010 (NL)

We are arranged in the space. Francis O'Shaughnessy tells us where we can sit – there, no further, that is good - and pauses. Sara Létourneau enters with two china teacups, complete with saucers. O'Shaughnessy

takes a pair of scissors and cuts a slit in his shirt. Something is bundled under the fabric, at the bicep. Létourneau puts her knees in the two tea cups – which have a clear liquid in them that I later learn is bleach – and stands, looking at us. She takes bread out of her bra and eats it. He takes bread out of the cut in his sleeve and eats it. They stand. She looks at the audience and he paces, both eating. Stand. Pace. Eat. Look at the audience, impassive. Repeat. It seems almost like a force-feeding, the way they keep on eating the dry bread without swallowing. Their mouths full. She starts to twirl her hair. Standing. Staring. Chewing. He takes out the scissors again and cuts the lock of hair that she has meanwhile twisted and held out. He puts the hair down his pants. This seems to break the monotony of the chewing. Each takes a tea cup and removes it from the saucer, placing it closer to the audience. Then they lean over the saucers, in concert, and open their mouths, dropping the bread balls they've been chewing onto the saucers with a plop. The bread action over, they move the plates to the side. An off-kilter invocation of domestic ennui.

To continue their portrait of dystopic gender relations and family life, Létourneau takes out a spool of red thread and a needle while O'Shaughnessy cleans the floor of breadcrumbs with a paper towel. He then walks slowly across with the cups, filled to the brim with bleach, doing his best not to spill, and places them to the side. Taking out a length of grey yarn, he ties each end to each of the teacup handles. Létourneau meanwhile has threaded five needles to the same thread. He cleans some more with the paper towel while she pins the needles to the wall in the shape of a house. A plaintive drawing against the gallery wall. O'Shaughnessy then undoes his zipper and gropes inside his pants, looking for something. Finally, he pulls out a flower. A daisy. The audience giggles. He does some improvised calisthenics - jumping jacks and push-ups. Bread crumbs are flying from his sleeve, littering the floor he has just cleaned. She stands inside the red-thread house and looks at him. Coyly she takes off her tights. Shoes. He drinks a sip of beer from an audience member. She puts on a pleated skirt. He takes off his T-shirt and puts on a long-sleeved one. Létourneau moves to the center of the space, bringing the thread with her, and O'Shaughnessy lets himself get caught in it.

He puts his head up her skirt and she sings How Long Has This Been Going On while he works at doing something up her skirt. Létourneau, the red spool of thread still in her hands, proceeds to wrap a thin line around her waist. As she sings she continues, round and round, the thin red line getting thicker and thicker. I could cry salty tears / Where have I been all these years / A little while, tell me now / How long has this been going on? With her tiny a capella voice and her French Canadian accent, she sings. All the while he continues to work under the skirt. There were chills, up and down my spine / Yes, there're thrills I can't define / Listen sweet, while I repeat / How long has this been going on? He comes out of the skirt, sighs as if exhausted, and removes the bag. Breaking the thread, she throws the spool away.

He puts his head up her skirt and she sings How Long Has This Been Going On while he works at doing something up her skirt. Létourneau, the red spool of thread still in her hands, proceeds to wrap a thin line around her waist. As she sings she continues, round and round, the thin red line getting thicker and thicker. I could cry salty tears / Where have I been all these years / A little while, tell me now / How long has this been going on? With her tiny a capella voice and her French Canadian accent, she sings. All the while he continues to work under the skirt. There were chills, up and down my spine / Yes, there're thrills I can't define / Listen sweet, while I repeat / How long has this been going on? He comes out of the skirt, sighs as if exhausted, and removes the bag. Breaking the thread, she throws the spool away.

At this point O'Shaughnessy places a cutout icon of a woman on the floor of the gallery. Turning, he proceeds to Létourneau, who is standing against the wall, in "customs search" position.

[all photos by Henry Chan]